|

Architecture

On this page:

back to top

Infrastructure

Source: http://loadrunner.uits.iu.edu/weathermaps/abilene/

Internet2 Abilene backbone. Click on the image to view current network status.

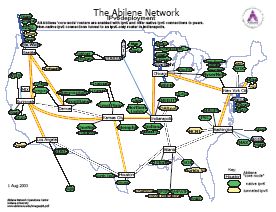

Abilene

At the core of Internet2 is a high-bandwidth backbone named

Abilene connecting eleven

regional sites across the United States. Fifteen high-speed fiber-optic lines connect

core sites in Seattle, Sunnyvale, Los Angeles, Denver, Kansas City, Houston, Chicago,

Indianapolis, Atlanta, New York, and Washington, D.C. The Abilene backbone consists of

13,000 miles of fiber optic cable and transfers about 1,600 terabytes of data per month.

Abilene is managed from a

Network Operations Center at Indiana University in Indianapolis

and is monitored 24 hour a day, 7 days a week.

vBNS

While Abilene serves as the primary backbone of Internet2, another network called vBNS

(very high performance Backbone Network Service) also contributes to Internet2. vBNS,

developed in 1995 by the National Science Foundation and MCI, connects several governmental

and university research institutions and initially served as the primary backbone of

Internet2. Abilene and vBNS now connect to each other, allowing users of either network

full connectivity to Internet2. In 2000, vBNS evolved into the commercial service

vBNS+.

Source: http://www.stanford.edu/group/itss-cns/i2/vbns.html

Bandwidth

Since its creation, Abilene has been continually upgraded to provide increased bandwidth and

higher performance. As of August 2003, Abilene is currently undergoing an upgrade from OC-48

(Optical Carrier level 28) to OC-192 (Optical Carrier level 192) connections. Optical Carrier

lines run over high-performance fiber optic cable and are commonly used in backbone networks.

An OC-1 line runs at 51.84 Mbps, and higher-level OC lines run at multiples of this speed.

Thus, OC-48 lines, which currently form slowest part of the Abilene backbone, run at 51.84 *

28 = 2488.32 Mbps, or 2.488 Gbps. Similarly, the next-generation OC-192 Abilene links provide

a maximum bandwidth of 10 Gbps.

The following map shows upgrade status of Abilene as of August 29, 2003. The solid red lines

are currently functioning OC-192 lines, the dotted red lines will be upgraded to OC-192 in late

2003, and the gray line between Indianapolis and Atlanta will remain an OC-48 link.

Source: http://loadrunner.uits.iu.edu/upgrade/pix/AbNgarTopo.pdf

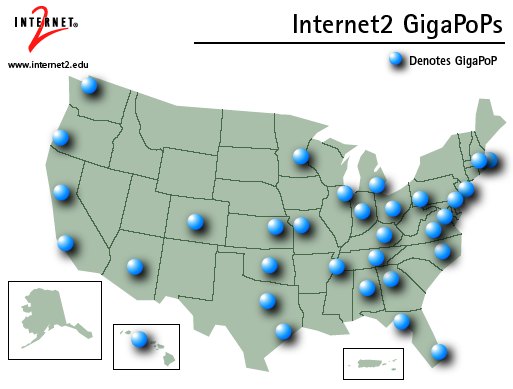

GigaPoPs

In addition to the core nodes of the Abilene backbone, Internet2 uses several regional gigaPoPs

to provide connectivity to multiple institutions. A gigaPoP, or gigabit capacity point of

presence, is intended to be a meeting place between the Internet2 backbone and up to 12

institutional networks. Some gigPoPs may also provide connectivity to additional networks.

The following map shows the 32 gigaPoPs connected to Internet2 as of September 2003.

Source: http://www.internet2.edu/resources/Internet2GigaPoPsMap.PDF

External Connections

Internet2 is not the only educational and research network in the world or even in the

United States. To allow Internet2 members to collaborate with institutions not connected to

Internet2, the Abilene backbone provides connections to many worldwide networks. The following

maps show the location of connection points between Abilene and other domestic and international networks.

Source: http://abilene.internet2.edu/images/abilene-fed-res-peers-title.gif

Source: http://international.internet2.edu/intl_connect/Intlpeering_Abilene.gif

back to top

Middleware

Middleware is the layer of software that mediates the connection between the network infrastructure

and the applications which use it. It acts as a standard for various services such as security and

directories, thus preventing cross-platform compatibility issues and ensuring a higher level of

reliability.

In today's Internet, applications need to provide these services themselves, and often end up

writing various competing and incompatible codes. The development of Middleware arose out of the

awareness of this need for a central system of standards to manage activities and provide services

on the Internet.

Middleware is also the name of the working group established under Internet2 to look into

developing this software interface. The group has since focused their attention on five key

sub-areas:

- Directories - they allow users and applications to search for information about other users

and applications on the network.

- Identifiers - they are labels for users, applications and other entities on the network. By

systematically allocating identifiers to entities on the network, it becomes easier to produce

applications which work with these entities. It also allows better protection of user privacy

and network security.

- Authentication - it is the process that ensures that the use of identifiers is valid and

secure. The main work is in studying various ways of verifying the identity of a user, such as

through passwords or biometrics.

- Authorization - it is the process which sets the tasks and information that the user is

permitted to access. For example, a scientist at a certain laboratory would be allowed to access

equipment and data from his workplace by means of his identifier.

- Public Key Infrastructure - it refers to a very promising but complex and hard-to-implement

set of techniques for electronic security. This security is achieved by the exchange of

electronic credentials known as certificates. Certificates form the basis on which the other

four sub-areas are built: they are stored in directories, tied with related identifiers, and

are applied in authentication and authorization processes.

back to top

Engineering

Engineering refers to the various projects which study the procedures and protocols that make

networking more efficient. Working groups looking into IPv6 (a new internet protocol), QoS (Quality of Service) guarantees, multicasting

and other issues have been established to date.

While there are currently no intentions to integrate the Abilene and vBNS networks with the mainstream Internet, these networks act as a platform

on which new age Internet applications and protocols are being developed and tested. It ensures

that such developments trickle down to the Internet in the smoothest possible manner.

Quality of Service

back to top

(click on the link above for a short flash presentation on QoS.exe)

Source: http://www.internet2.edu/resources/QoS.exe

Many of todayís advanced network applications such as video conferencing and telesurgery work

with large amounts of real-time data that needs to be sent quickly on dedicated channels

across the Internet without any loss. However, the Internet tends to treat all data

indiscriminately and packets of high priority information are frequently dropped as a result

of congestion from lower priority traffic such as emails.

Quality-of-Service (QoS) guarantees are created to solve this problem. Important data are tagged

to ensure that network routers send them down dedicated bandwidths. At the same time, less

important information are not dropped in times of congestion but queued to ensure that they are

eventually sent. This reduces the need to resend data when it fails to get through, and hence

lessens unnecessary congestion on the Internet.

There are many various forms of QoS guarantees that differ based on one or more of the following

parameters: bandwidth, delay, jitter, and loss. Bulky information with require high-speed

transmission such as pictorial intelligence information during a war may need a large bandwidth.

Real-time interactive online events such as telesurgery or video conferencing may require

communication with low delay and jitter. Intricate information such as detailed scientific

measurements may call for channels that minimize data loss and distortion.

The Internet2 QoS working group is looking into how these QoS guarantees can be implemented on

the technical level, and distributed effectively on the user level.

QBone Scavenger Service

The Internet2 QBone Scavenger Service (QBSS) is a network mechanism that lets users and

applications take advantage of otherwise unused network capacity, without substantially

reducing the performance of the default best-effort service class.

It is based on the idea that people sometimes send non delay-sensitive bulk data, such as data

from radio astronomy, during periods of low network traffic to avoid adding to the congestion

during busy times. QBSS takes the burden of deciding when to send the data off the user. It

creates a parallel virtual network that expands and contracts to make use of any spare network

cycles, all without affecting the flow of high priority traffic during transmission.

back to top

Multicasting

Today's Internet uses a model of communication known as unicast, where the data source creates

a distinct copy of data for every recipient. This creates a huge problem of network congestion

when many people try to access the same piece of information, such as the live telecast of a show,

at the same time.

Multicast is a method that solves this problem by sending only one copy of the information along

the network, and duplicating it at a point close to the recipients to minimize the bandwidth used

along a large part of the network.

Many different applications such as distance learning, video conferencing and digital video

libraries stand to benefit from multicasting. Multicasting has been deployed fully on the

Internet2 backbone networks Abilene and vBNS and its regional networks. It has been used to

deliver better-than-TV-quality video to thousands of users at the same time, and such technologies

are slowing trickling into the mainstream Internet.

back to top

IPv6

TCP/IP (Transmission Control Protocol/Internet Protocol) is the standard protocol suite used

for transmissions across the Internet. The Internet Protocol, or IP, is a standard in the TCP/IP

suite that enables data to reach a remote destination. When information is sent across the

Internet using IP, it is split into smaller units called packets that are sent separately to

the destination. The destination computer then receives these packets and pieces them back

together to form the original data.

In order for a packet to reach another computer across the Internet, it must have some way of

identifying the remote computer. One of the most important components of IP is an addressing

scheme that provides each computer on the Internet with a unique IP address. The IP standard

prefaces each packet transmitted with a small header that includes the source and destination

addresses of the packet. As a packet transverses the Internet, each router along the way looks

at the destination address in this header to determine where to send the packet next.

The Current Internet: IPv4

The current version of IP in use on the common Internet is version 4, or IPv4. An IP address in

IPv4 consists of 32 bits, usually divided into four octets and written in decimal as four numbers

between 0 and 255 separated by decimal points ñ for example, 10.10.243.21. The maximum number of

combinations this allows is easily computable as 2^32 or 4,294,967,296. In practice, however,

many fewer addresses than this are available. For example, all IP addresses with first octet 0,

10, 127, and 224-255 are reserved for special uses such as private networks, multicasting, and

experimentation, and are not assignable to individual computers on the public Internet.

As the Internet has grown, it has became apparent that the current IP addressing scheme does not

provide enough addresses to assign one to every device that will be connected to the Internet in

the future. Even if all 4.3 billion possible addresses were available, they would not be

sufficient. In addition to a growing number of Internet users worldwide, technical advances are

allowing more devices such as cell phones, PDAís, and household appliances to connect to the

Internet ñ and to do this each will need an IP address. In 1994, the Internet Engineering Task

Force (IETF) calculated that IP addresses could run out as soon as 2008.

One technique currently in use to help prevent this shortage is a technique called Network Address

Translation, or NAT. NAT allows multiple computers on a local network to share one IP address

used to connect to the Internet. Unfortunately, this means that other computers on the Internet

canít distinguish between these machines. If another computer tries to connect to the shared

address, it can only be connected to a single pre-configured machine. This means, for example,

that two computers running in a NAT system canít both run web servers because there is no way

for users on the Internet to distinguish between them. A much more convenient solution than NAT

would be to increase the number of available addresses by lengthening IP addresses beyond 32

bits.

The Future: IPv6

Several standards were proposed in the early 1990ís to replace the current version of IP with one

supporting longer address. One of these standards was adopted in 1994 and has become Internet

Protocol Version 6, or IPv6. Unfortunately, making the change is not easy. Unless they have

been upgraded to specifically support IPv6, most computers and routers on the Internet are

programmed to determine assume every packet uses the IPv4 header. This diagram shows the header

format of an IPv4 packet:

The header contains many pieces of information, but for this discussion only the source address

and destination address are of interest. As you can see from the diagram, computers and routers

expect to find the source address in the 13th through 16th bytes of every packet and similarly

the destination address in the 17th through 20th bytes. For IPv6 to replace IPv4, every device

on the Internet needs upgraded to recognize a new format. The next diagram shows the new header

format used in IPv6 packets:

As the diagram shows, the address size has increased by a factor of four to 128 bits. This

allows an immense number of addresses: 2^128, or 340,282,366,920,938,463,463,374,607,431,768,

211,456. Although just as with IPv4 a significant number fewer addresses will actually be

available, a study of the best and worst-case scenarios estimated that there will still be

between 1,564 and 3,911,873,538,269,506,102 usable addresses per square meter on the surface

of Earth. It is highly unlikely that these addresses will run out anytime soon.

A new scheme of representing these addresses has also been created. Rather than represent an

address as a series of octets in decimal form, the convention is to display IPv6 addresses as

8 4-digit hexadecimal values, such as 1080:0:0:0:8:800:200C:417A.

Another notable improvement in IPv6 is increased header efficiency. As the diagrams shows,

IPv4 devotes 16 bytes of the header to information other than the addresses, while IPv6 headers

have only 12 bytes of additional information. By decreasing the header overhead and improving

the way additional optional header fields are sent, IPv6 helps speed routing operations. Other

improvements in IPv6 include support for anycast addresses that can direct a packet to take a

specific route, improved multicast support, and additional security features.

IPv6 and Internet2

One of the goals in creating Internet2 was to test and implement improved networking technologies,

including IPv6. An IPv6 Working Group was formed within the Internet2 organization specifically

for this task. As the Internet2 backbone developed, care was taken to upgrade and choose equipment

to support the new version of IP. In addition, the working group aims to educate and motivate

Internet2 institutions to support IPv6 in their equipment and networks. Today, the Abilene

backbone provides full IPv6 support, as do many hosts connected to it. The following diagram

shows the status of IPv6 deployment as of August 2003. Click on the image to view a full-quality

PDF file of the map.

Source: http://www.abilene.iu.edu/images/v6.pdf

|

|

|