1. Effects of Technology on Population

Over the last few decades, technology has advanced at a rapid rate and spread around the globe. The affordability and accessibility of technology has brought many benefits, including better scientific research, improved quality of life, and a higher average life expectancy in a number of countries. Since many aspects of daily life are automated, people can focus on their careers and interests. As a result, in many technologically advanced societies, people are not only living longer, but are also having fewer children. This trend has led to a disproportionately large growth rate of the elderly population relative to the labor force. Since many people are living until old age and not enough children are born to make up the difference, there are fewer and fewer resources to take care of older generations.

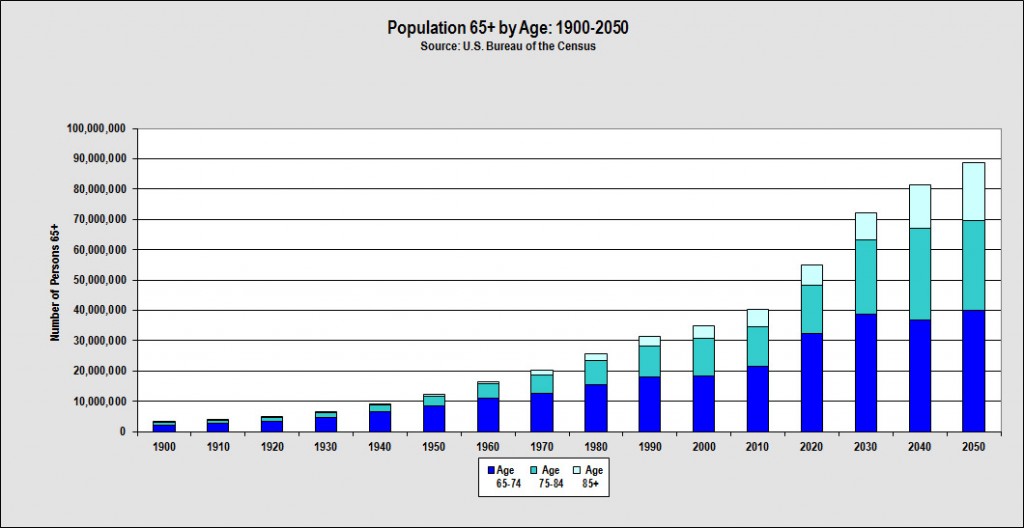

65 and older population projected to reach 72 million in 2030 (Administration of Aging: Department of Health and Human Services)

2. Problem in Japan

With the highest life expectancy in the world, Japan suffers from this problem more than any other country today. Nearly 30% of Japan’s population is over the age of 65, and with only about 1.2 births per woman, there are not nearly enough people entering the work force to make up for it.

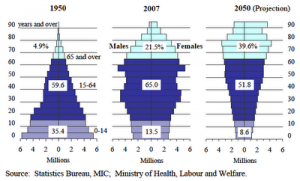

Japan's population pyramid is becoming skewed to reflect longer life expectancy and smaller birth rates

The population pyramid, which came to a natural peak in the 1950s, is now much heavier at the top. This is problematic not only because there are not enough people to take care of the elderly, but also because having such a large portion of the population in retirement drains GDP and the economy. The less people work the more debt accumulates, and low birth rates indicate that there will be less people to pay it off in the upcoming years.

As technology outpaces economic growth, this problem will soon play out on a large scale in many developed countries, and the current social systems designed to help aging generations will not be able to withstand the pressure. Today, the younger generations are making up for the inability of the older generations to provide labor. However, since the supply is thinning out, an alternative source of labor must be found.

3. Technological Answer

One proposed solution is to build robotic nurses that will help administer care and support to people in hospitals, care facilities, and homes. Japan’s hospitals are already in shortage of nurses, and according to Japan’s Machine Industry Memorial Foundation, the country could save 2.1 trillion yen (about $21 billion) in health care costs each year by using robots to monitor the nation’s elderly (Bartz). In fact, many robotics companies are already creating machines that look and speak like human beings (Android Demo), and several versions of the “Robotic Nurse” already exist. Today, robotic nurses are robots that help patients physically move around or perform simple tasks like taking vital signs or delivering medicine. Some robotic nurses serve as interfaces for doctors to use over distances to communicate with patients. However, a fully-integrated, fully autonomous robot nurse does not yet exist because of the

technological difficulty in creating an ethical and adequately error-free system under the highly uncertainty governing direct interaction with human beings.

4. Ethical Decision-Making

The main challenge in creating robotic nurses is the problem of programming a machine with a reliable set of ethics.

A robot nurse will have to make complicated decisions regarding its patients on a daily basis. Since its function will involve giving advice that will determine the health of human beings, it will need to have an ethical system that will allow it to properly carry out medical agenda while treating patients with respect. For example, if a robot is programmed to remind its patients to take their medicine, it needs to know what to do if the patient refuses. On one hand, refusing the medicine will harm the patient. On the other hand, the patient may be refusing for a number of legitimate reasons that the robot may not be aware of. For instance, if the patient feels ill after taking the medicine, then insisting on administering the medicine may turn out to be harmful. Leaving a reminder and ignoring any human response is also impractical because the robot will be replacing a human nurse, whose job is to make sure the patient is receiving proper care. Moreover, what if the patient agreed to take the medicine, and then forgot? Should the robot stay and monitor the patient until the medicine is taken, or is that a violation of privacy? When and how should the robot inform the doctor if anything goes wrong?

This scenario is an everyday situation that human nurses navigate with ease. The human brain can assess a situation not only based on data that it directly receives through its senses, but it can also logically process other signs, such as the look of a person or the intonation of a response. If there is not enough data to make a decision, a human can figure out which questions to ask in order to receive more information. Humans also have a complicated ethical system that is able to not only weigh the good against the bad, but is also able to make judgments about the degree of benefit of a given course of action. Robots cannot make decisions on such a level. Current technology only allows them to force a “yes” or “no” decision regardless of how much information is available. This is clearly not an adequate system for advanced ethics, so a new approach to decision making must be found.

5. Automated Decisions

Before robots can make decisions for humans, they will need to be able to tackle ambiguous circumstances. According to senior researcher Dr. Gert-Jan Lokhorst, “Sets of moral standards can be inconsistent, incomplete, or inappropriate in view of other sets of standards; it would therefore desirable that robots equipped with such standards were to some extent able to reason about them—in other words, if they had some capacity for meta-ethical reasoning” (Computational Meta-Ethics). If robots can not only distinguish right from wrong, but also reason about right and wrong through “computational meta-ethics,” then they will be one step closer to making decisions where normal protocol may not result in a desirable outcome. Lokhorst proposes that the robot will have several formal moral reasoning modules that will outline protocols and permissions, as well as a module that will computationally reason about its decisions. (Lokhorst’s Proof).

Another approach has been proposed by the IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man and Cybernetics. In order to cope with “relatively unstructured, changing settings,” the IEEE proposes the Information-Gap Theory approach: “Information-Gap Theory is an approach to decision-making under epistemic uncertainty – uncertainty due to lack of complete knowledge about modeled relationships.” An algorithm using this method will require a robot to first test its inputs and determine whether they are adequate to solve the given problem. If not, the robot will need to make decisions based on what additional information it needs and how it will acquire it. The example mentioned in the study ( Case Study ) follows the decision of a robot trying to climb a slippery hill while carrying a load. Instead of deciding whether to climb or not, the robot decides whether the decision to climb or not can be made at all. This is very similar to Lokhorst’s computational-meta-ethics approach.

Lets go back to the robot nurse that asks a patient to take his or her medicine and receives a negative answer. If the robot can determine that their negative response is not enough information to accept the response or make a new demand, the robot could make a better decision. For example, if the robot finds out that the patient is running a fever or is feeling sick, then it could possibly notify a doctor, which will be a much better decision.

Researchers at the University of Connecticut have been looking into making a robot that makes ethical decisions. Watch the following video for their findings:

When humans are faced with unclear decisions, they can think about it and recognize the need for more information. Robots however, tend to make decisions regardless of the circumstances based on pre-programmed protocols. These algorithms of meta-decision making will allow robots to “think” about the environment as well as the decision at hand and find solutions that are more consistent with human standards.

6.Japan’s Nurse Robots

As of today, robot nurses do not yet possess this level of sophistication. Current prototypes for robot nurses are designed as assistants, and no fully integrated autonomous system exists.

Japan, which is the current leader in robot nurse production, has several robots that address different needs in the medical community. One such robot is called RIBA, which stands for “Robot for Interactive Body Assistance.” RIBA can lift a person up to 135lbs from a lying or sitting position and move them to another location. RIBA has strong arms with advanced tactile sensors that prevent slipping. It is also equipped with two cameras and two microphones so it can follow cues from an operator. RIBA looks like a big teddy bear, which is meant to calm patients, but could also be unsettling to some. With the current weight limit, this robot will have to consider the consequences of lifting its patients. What happens if the weight is at 140lbs? Is this unmanageable, or alright if a nearby nurse gives approval? How should a robot balance its own best interest as well as the best of interest of its patients?

Japan-based robot maker Kokoro has focused on a different area of research with Actroid-F. This robot is modeled after a human female and can move its eyes, eyebrows, mouth, head, neck. Actroid-F is a tele-robot that can be controlled by a remote operator, whose expressions and speech it can mimic very accurately. This robot is also not autonomous, but it looks and interacts with patients as a human. Kokoro reportedly announced plans to sell 50 units to museums and hospitals to serve as receptionists or surveyors. Since Actroid-F is not yet autonomous, she will not need to decide ethical problems on her own. However, the operators will have to decide where surveillance crosses privacy boundaries, and whether interaction with humans beings through a robotic shell deserves the same rules of respect as does conversation between two people.

7. Pearl

In the U.S., researchers from the University of Michigan, University of Pittsburg, and Carnegie Mellon University are working on a Nursebot called Pearl. Pearl is an assistant robot like its Japanese counterparts, and it serves to remind people about routine activities as well as guide the elderly through their environment (Jajeh). Pearl has many sensors that help with navigation and recognition of audio and video input, as well as a touch screen interface, and software for the various tasks that it can do. It is a great technological tool for helping cognitively or physically disabled people get through day-to-day tasks.

The Autominder feature which schedules reminders is a sophisticated piece of software that incorporates some of the meta-decision making discussed above. It consists of a

- Plan Manager (stores and updates person’s schedule)

- Client Modeler (tracks execution by recording observable activities)

- Personal Cognitive Orthotic (reasons about disparities, decides when to issue reminders)

The PCO stores a record of a person’s habits and makes decisions based on how likely the reminders will be effective and when they will be executed. This is a sophisticated algorithm that incorporates meta-ethics into decision-making by calculating the potential benefit of each decision to both the patients and the doctors’ agenda. For example, if a client has a history of watching a TV show at a certain time, reminding them 5 minutes earlier will be more effective than reminding in the middle of the show, when they are more likely to forget.

Pearl also has sophisticated navigation algorithms that take into account the map of its surroundings and a way to modify its speed based on how fast its client is moving. This is a very useful tool because it assisting people who move at slow paces is a very time consuming task for human employees. Pearl allows other staffers to offer their help where it is needed.

Pearl has been tested at the Longwood Retirement Community in Oakmont, PA, and has received very favorable reviews by the residents. It operates in a relatively un-intrusive manner, and is made to look like a robot, so patients do not feel uncomfortable around a humanoid machine. Pearls decision making is still at a relatively primitive level, but the residents of this community are already saying that they appreciate the considerate timing of her reminder program.

8. Successful Integration

The main difference between human and robot decision-making lies in how each approach situations where information is scarce or ambiguous. The human brain is much more adaptive and can discriminate obvious decisions from situations that require a little more thought. Computers are slowly getting to this point through more flexible algorithms that focus on the quality of decision-making as opposed to simply the “yes” or “no” decision itself. This technology is still many years away, but as computers become more sophisticated it is essential that they remain constantly tested. A successful integration of intelligent, ethical robots in society requires plenty of field-testing in unpredictable real-life environments. Since it is inconvenient, and sometimes dangerous, to deploy untested autonomous machines near humans, these robots should be introduced as assistants to humans with limited functionality until testing is complete. Newly created machines should only operate under strict supervision of human staff-members and only given more responsibility when their data sets and learning algorithms become more sophisticated.

Personal care robots will have to work closely with humans, which will require a certain level of trust. If robots are first used as mechanical tools (as in the example of RIBA or Actroid-F), and then slowly deployed as assistants with limited tasks (such as Autominder system of Pearl), then people will be more open to the idea of having autonomous machines take care of their basic needs. Robots will automate some of the mundane day to day problems of scheduling, mobility, etc., but human care-givers will not go away. Just like recent advances in technology have freed up many hours in menial chores, these autonomous machines will free up more time for human workers to concentrate their labor where it will be more useful. In the near future, robots will not have to make ethical decisions on a very big scale. In fact, robots can help automate many aspects of care-giving that involve small ethical decisions that will soon be feasible to compute. However these machines can only be successfully integrated if society can adjust to a new way of interacting with technology.