The Need for Autonomous Weapons Systems

In the heat of battle, fear, anger, and vengefulness can cause even the most trained soldiers to commit war crimes that violate ethical standards laid down by Geneva and other international conventions. There is a possibility that machines may one day reach a point where they make more ethical decisions on the battlefield than humans can in the short time they are given. As technology advances and reaction time curves steepen, we are no longer safe behind our conventional weapons from 100 years ago. We are forced to progress to compete with the technology of the rest of the world. Wartime decisions are required faster than our minds can process the complex situation of war, giving rise to human error, and the reaction time threshold our soldiers must meet will only become quicker as technology advances. We must not be blind to a possible future where autonomous weapons replace human, and computers decide when to pull the trigger. Is such an invention ethical? Can we trust machines with such extreme responsibility, the responsibility of human life?

The Current State of Weapons

Trusting computers with our nation’s defenses is nothing new. The military already depends largely on computers to calculate possible nuclear scenarios, to control missiles, and to fly remotely piloted vehicles (RPVs). The military armed fighter drones with weapons long ago, but thus far none have been deployed unmanned. Robot drones, mine detectors, and sensing devices are common on the battlefield but require direct control by humans. There are many reasons use such devices. RPVs allow military personnel to sit far away from the multitude of dangers on the battlefield and control the war. RPVs prevent the loss of human life that would occur should we put soldiers on the battlefield instead of behind the controllers. The next logical step is to replace the human controllers with autonomous systems that govern the fighting behavior of drones. The question is whether this an ethical choice and what are the ramifications of such a decision? How much testing must be done before we decide the autonomous warriors are prepared for deployment?

Obstacles to Overcome Before Autonomy

Because technology is advancing faster than ever, we must begin to rely more heavily on computerized systems, especially during times of war. Robots do not have an instinct of survival and will not lash out in fear. They show no anger or recklessness because they are not programmed to. As AI improves, we will see computers that can carry out orders more efficiently and reliably after they are programmed to do so, and they will not think twice about their orders. This will be much less expensive than hiring soldiers and possibly even more ethical. According to the Office of the Surgeon (2006), “Only 47 percent of the soldiers and 38 percent of Marines agreed that non-combatants should be treated with dignity and respect” (Office of the Surgeon, 2006, p. 35). Human fear, vengefulness, and anger leads to a large number of unethical war crimes. These psychological shortcomings on the theater of war make a good argument for decision making to be placed in the hands of machines. Also, off the stage, humans can be even more vicious when they are not in the field of battle themselves. By remotely piloting UAVs, with controllers similar to those on the Xbox, killing is little more than a video game to many soldiers. Is this what we want? Although robotic systems with human controllers can already accomplish many military objectives, pushing decision making to robots will reduce the number of casualties.

In order to deploy autonomous killers though, we must weigh the costs and benefits over many issues. The cost of human life is the largest cost any technology can accrue. If we are not certain these machines work flawlessly and ethically, deployment is out of the question. Many argue that it will never be possible to field such robots. However, it is difficult, even for weapons technology experts to predict the future of autonomous machines because technology is changing so rapidly. Computer scientist Allen working on autonomous robots at Yale says “making robots sensitive to moral considerations will add further difficulties to the already challenging task of building reliable, efficient, and safe systems.” His doubts are echoed by the current state of computer vision. The problem of seeing people has not even been solved (in general) by computers (it is only solved for specific scenarios to a high degree of accuracy). But how can we expect computers to recognize a wounded individual or a white flag being held up by the enemy if we can’t even recognize people yet? Even if the algorithm works 99.9% of the time (which no one has attained), the other .1% will mistakenly result in a civilian casualty, an unaffordable cost

At best, AI gives robots conditional contingencies to deal with unforeseen circumstances. But the number of such circumstances that could occur simultaneously in military encounters is vast and could cause chaotic robot

At best, AI gives robots conditional contingencies to deal with unforeseen circumstances. But the number of such circumstances that could occur simultaneously in military encounters is vast and could cause chaotic robotbehavior with deadly consequences.

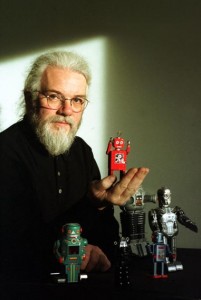

Dr. Noel Sharkey, Chair of Dept. of CS University of Sheffield England

This does not even begin the question of computer decision making. Autonomous systems must not only be able to distinguish targets, but they must be able to discern when is an appropriate time to fire. There are so many circumstances to code for, it would be difficult to catch them all, and although we could learn by trial and error, this would not be acceptable because of the cost of a trial. Noel Sharkey claims “At best, AI gives robots conditional contingencies to deal with unforeseen circumstances. But the number of such circumstances that could occur simultaneously in military encounters is vast and could cause chaotic robot behavior with deadly consequences.” We cannot predict all the circumstances that will occur and thus should not field such robots, Sharkey suggests. However, Sharkey (let alone anyone) cannot predict the future of the technology, and while it may not be appropriate at the present time, should we be able to develop an AI that thinks as we do, or a new framework that is capable of doing better than the human mind on the battlefield, we would surely see its use.

We will never be able to rely on computers 100% of the time. “The more the system is autonomous then the more it has the capacity to make choices other than those predicted or encouraged by its programmers” (Sparrow, 2007, p. 70). Computers are complex and not deterministic. However, people are not deterministic either, as evidenced by the large number of war crimes committed and military brutality statistics. Even soldiers have trouble telling who is a civilian and who is not. Computers can perform gait analysis and eventually more sophisticated algorithms involving emotion recognition etc as computer vision advances and will one day surpass humans in this area of judgment.

The task is still difficult though, and we are many years from being able to compute everything that is needed to brave the battlefield without the insight of human instinct and built-in conscience. An example: Pilots are given the location of enemy troops, infrastructure, and leaders. They are programmed with given the rules of engagement and rules that govern when they can and cannot engage their target. The goal of programming autonomous systems, and the most difficult task is to integrate the rules of war with “the utilitarian approach – given military necessity, how important is it to take out that target?” (Borenstein) Robots will need to recreate the ethics given our standards and rules. While it might be ethical to attack an important terrorist leader in a taxi in front of an apartment building, it could be unethical to engage in a temple or other sacred site. Machines must filter out such ethical problems and learn to think as we do because we simply cannot code for every case. Sharkey accurately notes, “an AWS can in principle be programmed to avoid (intentionally) targeting humans, but theory and reality on the battlefield are two very different things,” so we must remain cautious as we approach a robotic battlefield. (Sharkey, “Robot wars”, 2007).

A Possible Future Safeguarded By Autonomous Weapons

Despite the harsh criticisms of Sharkey and Sparrow and the pessimistic views of Allen regarding autonomous robots, there are many who believed they can be fielded. Daniel Dennett, a professor at Tufts University, states “If we talk about training a robot to make distinctions that tract moral relevance, that’s not beyond the pale at all.” We cannot expect a perfect machine, as long as we can produce one better than the human soldier, we can release it. Arkin states optimistically that, “It is not my belief that an unmanned system will be able to be perfectly ethical in the battlefield. But I am convinced that they can perform more ethically than human soldiers are capable of.”

“My intention in designing this is that robots will make less mistakes—hopefully far less mistakes—than humans do in the battlefield.”

Dr. Ronald Craig Arkin, American roboticist and roboethicist

To support this claim, Arkin says that robots can indeed be programmed to be empathetic. Robots need to be programmed with rules about when acceptable to fire on a tank and must learn how to perform complicated, emotionally fraught tasks, such as distinguishing civilians. However, when we fill a robot’s decision tree with rules based on humane principles, such as those of Geneva, we endow the robot with a kind of empathy because its rule set is based on principles stemming from morals. We must simply be careful to fill a robot with such rules. Also, imposing harsh restrictions on when to fire, although possibly limited the robot’s usefulness, will prevent casualties. For instance, drawing from agreed on Laws of War, Arkin presents a list of mission guidelines that could be programmed into robots, including sets of restrictions that would prevent them from harming civilians. This can be viewed similarly to the mantra of the court system, that they would sooner let 1 villain go than jail 10 innocent people. If there are many checks that must pass before pulling the trigger we can create a civilian-safe autonomous robot. The future for this is hopeful, some experts believe robots will be more reliable at determining which is civilian and which is not. Again, gait analysis and emotion perception will bloom. Eventually robots may have more acute senses than humans will.

Another argument that has not been touched on is the security of autonomous systems compared to the remotely piloted systems currently in use. Remotely piloted systems, although extremely secure, are potentially vulnerable to hacks. Hackers can already break into military computers, and although difficult, there is no way we can say for certain hackers could not obtain these very deadly weapons because they are remotely driven. Even with extensive protection, it is impossible to secure a network, and should RPVs ever fall into the hands of anyone but the military operators, the States would be in trouble. Autonomous systems, however, are much less susceptible because they presumably would have all orders and logic programmed far ahead of time and thus would not be possible to commandeer because they would not rely on the base station.

Conclusion

The replacement of Remotely Piloted Vehicles (RPVs) by autonomous systems is imminent. It is only a matter of time until we hand weapons over computers they can outperform soldiers. Computers do not suffer from fear or the instinct to survive and can eventually be trained to behave more ethically than soldiers. As computer vision, simulation, and robotics advance, we could very well witness the day that autonomous robots are deployed. We are still a good distance away from being able to accurately detect civilians, and prepare for every situation in the complex scenario of war. Extensive testing to ensure there will be very few costly human lives will allow us to transfer the responsibility of warfare from possibly unreliable soldiers much quicker, accurate, machine hands and thereby reduce casualties., There should be a heavy criteria that must be met on the front of ethical reasoning before we deploy such robots because the responsibility they hold involves human life. We must ensure the robots can make ethical decisions in the place of human oversight. With the development of technology we will one day develop safe, reliable, efficient systems that can protect the lives of military youth and civilians alike.