|

Basic Overview

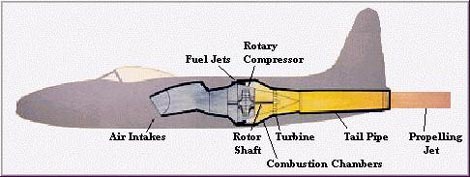

The image above shows how a jet engine would be situated in a modern

military aircraft. In the basic jet engine, air enters the front intake and

is compressed (we will see how later). Then the air is forced into

combustion chambers where fuel is sprayed into it, and the mixture of air

and fuel is ignited. Gases that form expand rapidly and are exhausted

through the rear of the combustion chambers. These gases exert equal force

in all directions, providing forward thrust as they escape to the rear. As

the gases leave the engine, they pass through a fan-like set of blades

(turbine), which rotates a shaft called the turbine shaft. This shaft, in

turn, rotates the compressor, thereby bringing in a fresh supply of air

through the intake. Below is an animation of an isolated jet engine, which

illustrates the process of air inflow, compression, combustion, air outflow

and shaft rotation just described.

The

process can be described by the following diagram adopted from the website

of Rolls Royce, a popular manufacturer of jet engines.

This process is the essence of how jet engines work, but how exactly does

something like compression (squeezing) occur? To find out more about each

of the four steps in the creation of thrust by a jet engine, see below.

SUCK

The engine sucks in a large volume of air through the fan and compressor

stages. A typical commercial jet engine takes in 1.2 tons of air per second

during takeoff—in other words, it could empty the air in a squash court in

less than a second. The mechanism

by which a jet engine sucks in the air is largely a part of the compression

stage. In many engines the

compressor is responsible for both sucking in the air and compressing it. Some engines have an additional fan that

is not part of the compressor to draw additional air into the system. The fan is the leftmost component of the

engine illustrated above.

SQUEEZE

Aside from drawing air into the engine, the compressor also pressurizes the

air and delivers it to the combustion chamber. The compressor is shown in the above image just to the left of

the fire in the combustion chamber and to the right of the fan. The compression fans are driven from the

turbine by a shaft (the turbine is in turn driven by the air that is

leaving the engine). Compressors can achieve compression ratios in excess

of 40:1, which means that the pressure of the air at the end of the

compressor is over 40 times that of the air that enters the compressor. At full power the blades of a typical

commercial jet compressor rotate at 1000mph (1600kph) and take in 2600lb

(1200kg) of air per second.

Now

we will discuss how the compressor actually compresses the air.

As can be seen in the image above, the green fans that compose the

compressor gradually get smaller and smaller, as does the cavity through

which the air must travel. The air

must continue moving to the right, toward the combustion chambers of the

engine, since the fans are spinning and pushing the air in that direction. The result is a given amount of air

moving from a larger space to a smaller one, and thus increasing in

pressure.

BANG

In the combustion chamber, fuel is mixed with air to produce the bang, which

is responsible for the expansion that forces the air into the turbine.

Inside the typical commercial jet engine, the fuel burns in the combustion

chamber at up to 2000 degrees Celsius. The temperature at which metals in

this part of the engine start to melt is 1300 degrees Celsius, so advanced

cooling techniques must be used.

The combustion

chamber has the difficult task of burning large quantities of fuel,

supplied through fuel spray nozzles, with extensive volumes of air,

supplied by the compressor, and releasing the resulting heat in such a manner

that the air is expanded and accelerated to give a smooth stream of

uniformly heated gas. This task must be accomplished with the minimum loss

in pressure and with the maximum heat release within the limited space

available.

The amount of fuel

added to the air will depend upon the temperature rise required. However,

the maximum temperature is limited to certain range dictated by the

materials from which the turbine blades and nozzles are made. The air has

already been heated to between 200 and 550 °C by the work done in the

compressor, giving a temperature rise requirement of around 650 to

1150 °C from the combustion process. Since the gas temperature

determines the engine thrust, the combustion chamber must be capable of

maintaining stable and efficient combustion over a wide range of engine

operating conditions.

The air brought in by

the fan that does not go through the core of the engine and is thus not

used for combustion, which amounts to about 60 percent of the total

airflow, is introduced progressively into the flame tube to lower the

temperature inside the combustor and cool the walls of the flame tube.

BLOW

The reaction of the expanded gas—the mixture of fuel and air—being forced

through the turbine, drives the fan and compressor and blows out of the

exhaust nozzle providing the thrust.

Thus, the turbine has the task of providing power to drive

the compressor and accessories. It

does this by extracting energy from the hot gases released from the

combustion system and expanding them to a lower pressure and temperature. The continuous flow of gas to which the

turbine is exposed may enter the turbine at a temperature between 850 and

1700 °C, which is again far above the melting point of current

materials technology.

To produce the

driving torque, the turbine may consist of several stages, each employing

one row of moving blades and one row of stationary guide vanes to direct

the air as desired onto the blades. The number of stages depends on the

relationship between the power required from the gas flow, the rotational

speed at which it must be produced, and the diameter of turbine permitted.

The desire to

produce a high engine efficiency demands a high turbine inlet temperature,

but this causes problems as the turbine blades would be required to perform

and survive long operating periods at temperatures above their melting

point. These blades, while glowing red-hot, must be strong enough to carry

the centrifugal loads due to rotation at high speed.

To operate under these conditions, cool air is forced out of many small

holes in the blade. This air remains close to the blade, preventing it from

melting, but not detracting significantly from the engine's overall

performance. Nickel alloys are used to construct the turbine blades and the

nozzle guide vanes because these materials demonstrate good properties at

high temperatures

|