The Gilded Age, generally defined as the period following the Civil War, although more specifically between the election of Rutherford Hayes and the end of reconstruction in 1976 and the Panic of 1893, was a time of immense development in American history. The economic scars of the Civil War had started to heal, even though the social scars were still visible. The economy grew dramatically due to the effects of industrialization and new forms of economic organization, and immigration increased from Eastern Europe, creating a strong trend toward urbanization and diversification.

The Gilded Age was also a period of immense graft and corruption, a theme that would be a mainstay of journalistic reporting throughout the era. The federal bureaucracy became ever more clogged with political appointees in sinecures, expanding the spoils system that was the hallmark of the earlier Andrew Jackson administration in the 1830s. Furthermore, political machines drove the politics of major metropolitan cities, and used a system of corruption to ensure the election of desired candidates.

Newspapers would play a crucial role in exposing scandals and investigating the wrongdoing of public officials. However, the ethos of journalism of the time was very different from journalism in the modern era. Newspapers commonly took strong political stances, which was reflected in their reporting. Major newspapers were associated with one of the political parties or a particular social movement. Scandals, therefore, were often unearthed by journalists opposed to the policies of a particular politician.

The presidential administration of Ulysses S. Grant is widely considered one of the most corrupt in history, although Grant himself is often considered a more minor player in the on-going scandals that plagued his time in office. There were more than a dozen notable scandals during his administration, but this article will focus on a representative case in this report: the Whiskey Ring.

The Whiskey Ring (1875) was a tax evasion scheme developed by the newly-empowered liberal Republican political machine in Missouri. The schemers bribed and cajoled administrators in every phase of the production of whiskey to underreport their numbers to avoid paying the whiskey tax – and therefore significantly increasing their profits. The money was then diverted to the local political machine, to increase its power over potential rivals.

The Whiskey Ring (1875) was a tax evasion scheme developed by the newly-empowered liberal Republican political machine in Missouri. The schemers bribed and cajoled administrators in every phase of the production of whiskey to underreport their numbers to avoid paying the whiskey tax – and therefore significantly increasing their profits. The money was then diverted to the local political machine, to increase its power over potential rivals.

The scandal was revealed in a series of investigations by Myron Colony, the commercial editor of the St. Louis Democrat, a paper opposed (perhaps obviously) to the Republican machine. Given his position, he was able to request figures from the different stages of the whiskey production process, eventually discovering the fraud when he reconciled the numbers. The story received immediate attention from across the country, and helped to usher in the end of reconstruction following the 1876 election.

The Whiskey Ring was not the most notable scandal in the immediate post-Civil War period, a title that is generally given to the enormous Crédit Mobilier scandal. Here, the U.S. Congress approved funds designated to the Union Pacific Railroad to build the first transcontinental railroad, but the funds were partially diverted to the Crédit Mobilier company and also used to bribe congressmen. Almost $50 million in funds were profited, an amount today that equals around $700 million after adjusting for inflation.

Newspapers played a crucial role in exposing the scandal. The Sun, a conservative newspaper in New York, received information about the diverted funds and the central role that congressman Oakes Ames took in the scam’s design. The newspaper was opposed to the reelection of Grant as president in 1972, and used the scandal to target him and his administration in reports throughout the election (Grant was uninvolved in the scandal himself).

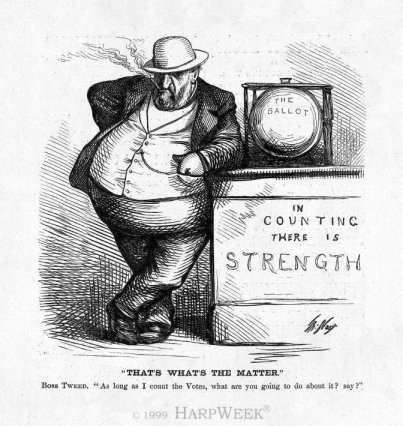

The level of corruption in national politics was perhaps moderate compared to the political machines that controlled the major urban areas of the country. No machine was more notorious than Tammany Hall, which controlled New York City politics for more than a century, and particularly under William Tweed in the post-Civil War period.

Newspapers reported the lurid details of the corruption and graft, but it was the political cartoons drawn by Thomas Nast that were permanently etched in the minds of citizens. Nast, a Republican and a cartoonist for Harper’s Weekly, was deeply disturbed at the level of corruption in the Tweed administration and began a campaign to discredit him. His caricatures of Tweed are very famous in American history, and the attacks discredited Tweed, who eventually lost an election and was later indicted.

Newspapers throughout this era, while staunchly partisan, were important fora to communicate prominent issues to the public. The enormous corruption provided instant fodder for the press, but it also ensured that newspapers and journalists upheld the ideals of the fourth estate – to question government and to keep it accountable.