Hands-on Experience with Devin: Reflections from a Person Building and Evaluating Agentic Systems

Updated on April 4th: We now discuss the human–AI collaboration aspect in software engineering more formally in Sections 3.3, 4.1.2, 4.2.3, and 4.3.4 of Challenges and Paths Towards AI for Software Engineering.

Last week, we shared our recent preprint titled “Collaborative Gym: A Framework for Enabling and Evaluating Human-Agent Collaboration”. Shortly afterward, a blog post titled “Thoughts On A Month With Devin” appeared at the top of my social media feed (smart algorithm :). This post immediately resonated with me—not only because we’ve also tried to use Devin (a coding agent product) to prepare the upcoming release of the Collaborative Gym codebase (WIP, the environment interface is available in this repo), but also because the cases in the blog’s appendix closely align with the findings presented in our paper and my recent thinking.

Inspired by this, I thought it would be worthwhile to dive deeper into why these agents often fail to meet real user needs and to share what currently excites me.

Tension: Benchmark Success v.s. In-the-Wild Disappointment

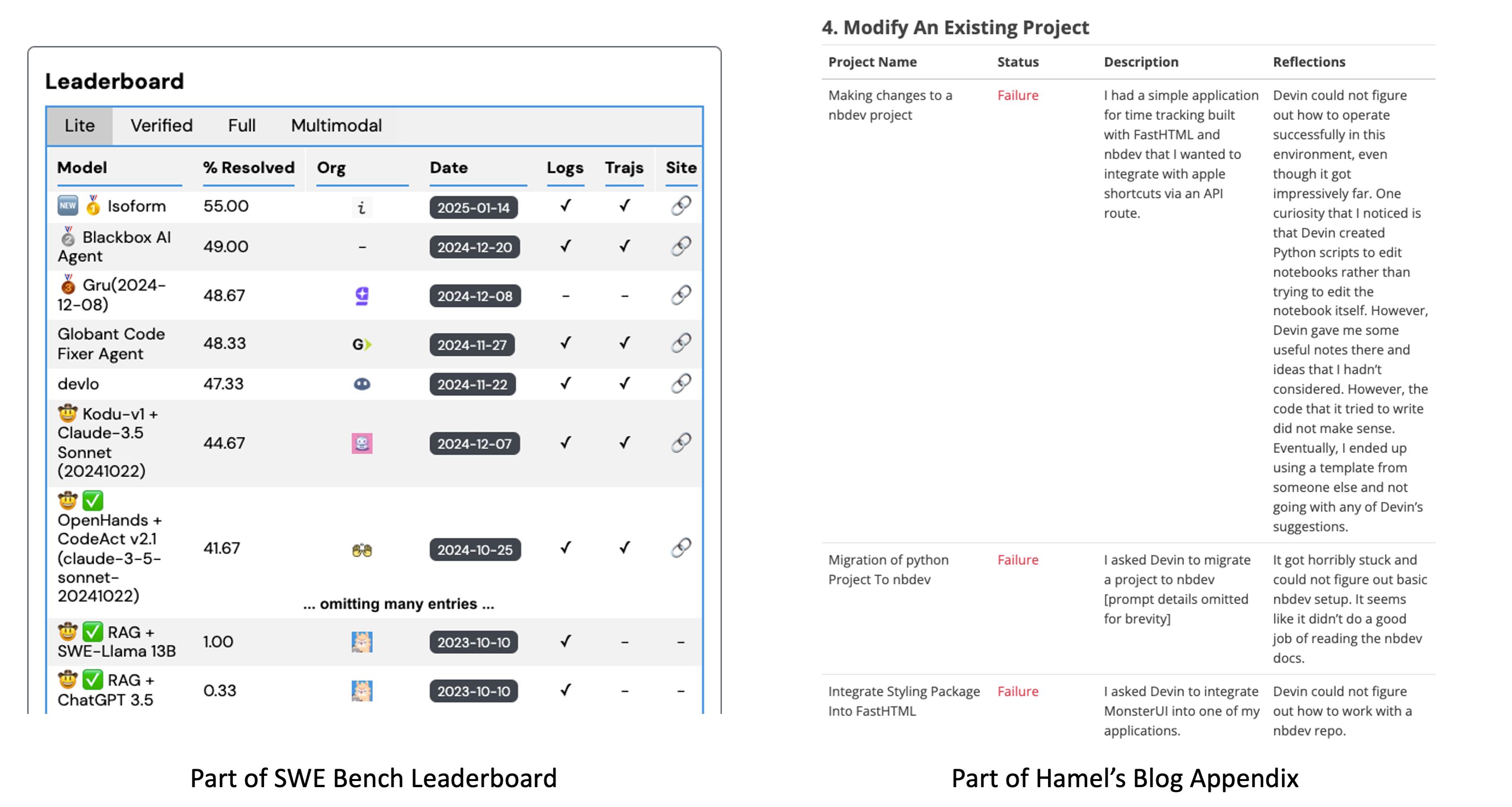

Despite the rapid progress in agent benchmark results, there’s a growing disconnect between those numbers and real-world user satisfaction. For example, performance on SWE-Bench Lite has skyrocketed from 0.33% on October 10, 2023, to 55% at the start of 2025, with new sota coming out almost weekly. However, Hamel’s blog post highlights a stark contrast: Devin, a coding agent developed by a highly regarded startup with $21 million in Series A funding, succeeded in only 3 out of 20 tasks during their trial.

This mismatch isn’t unique to coding agents like Devin. Similar disappointments have emerged in the context of web agents and computer-use agents, even around the excitement on releases from several renowned companies.

Challenge: Deep Dive Into Devin’s Failure Cases

We decided to try out Devin as soon as it became generally available for two main reasons:

- Its website advertises Devin as a “collaborative AI teammate.”

- It offers asynchronous interactions rather than rigid, turn-based exchanges.

During our one-month subscription, two individuals—myself (the primary developer of the repository) and Arjun (an undergrad who just started working together)—used Devin the most.

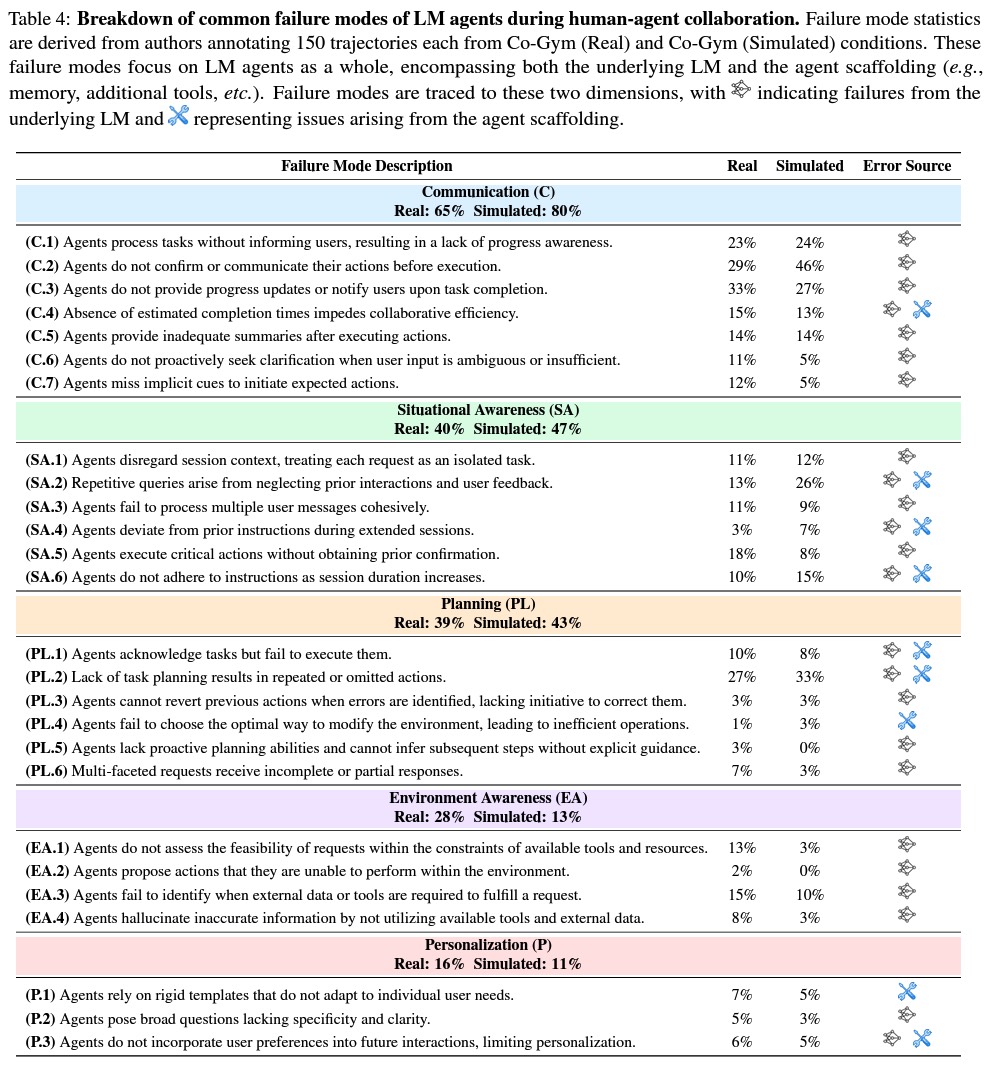

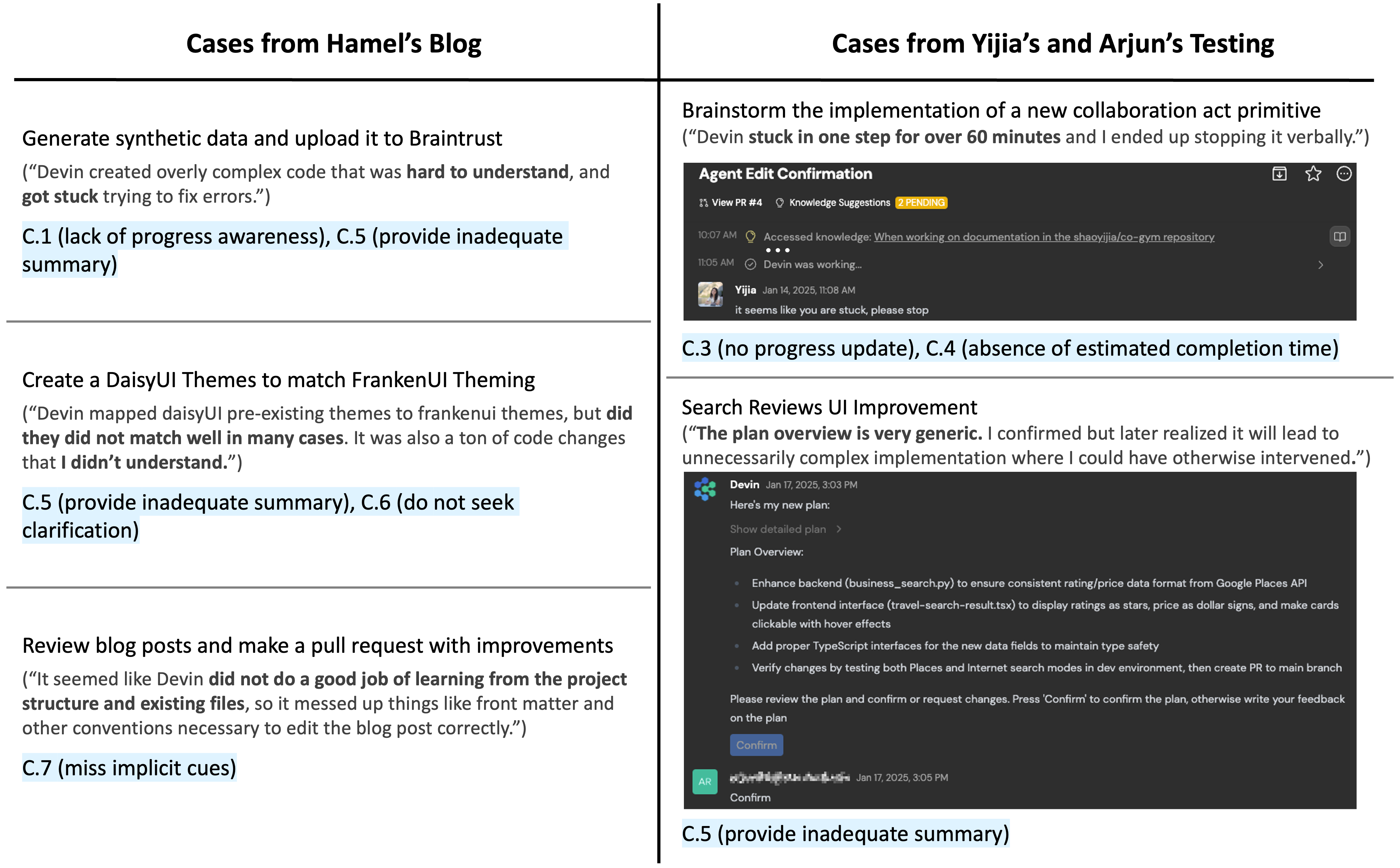

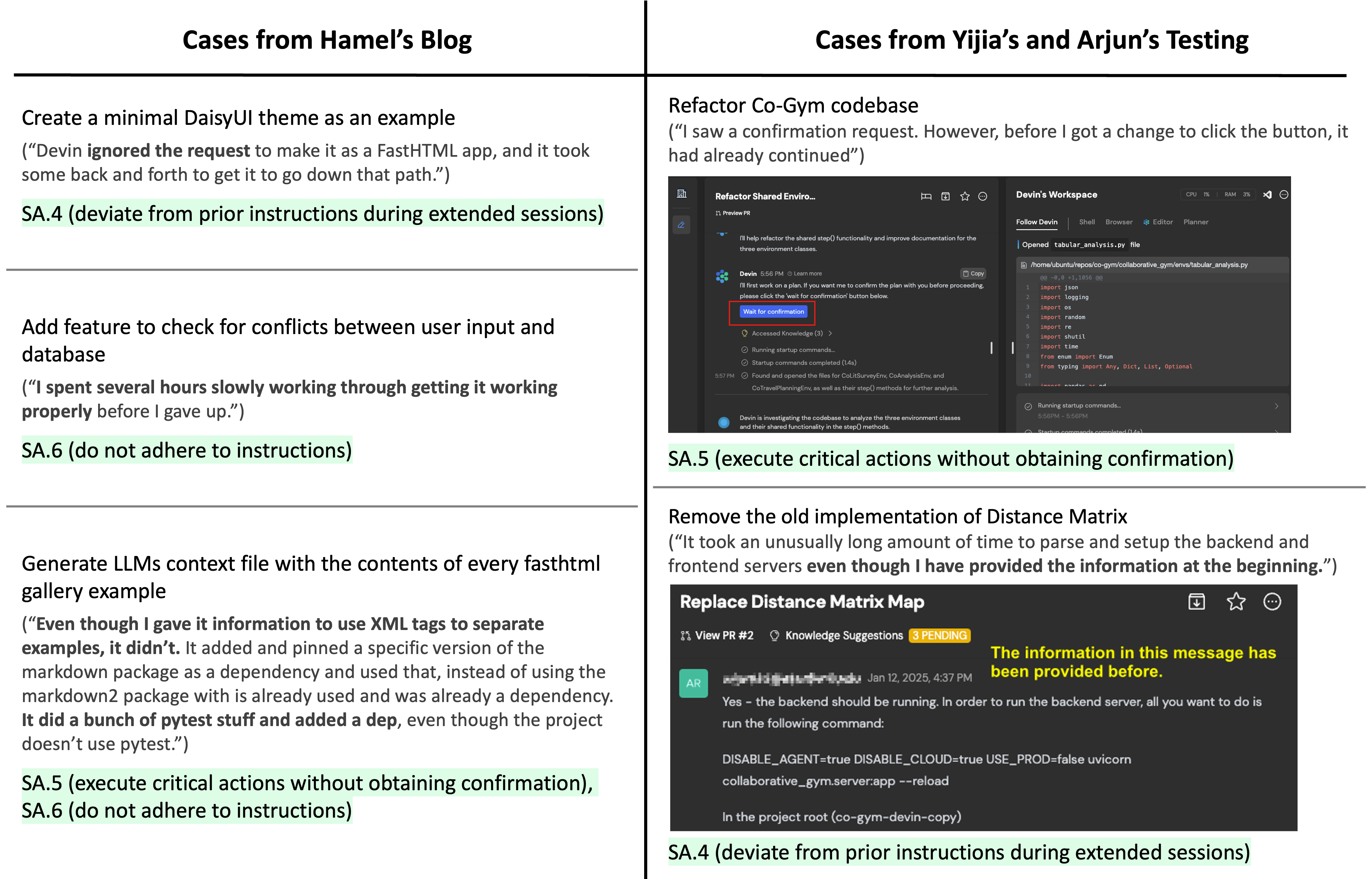

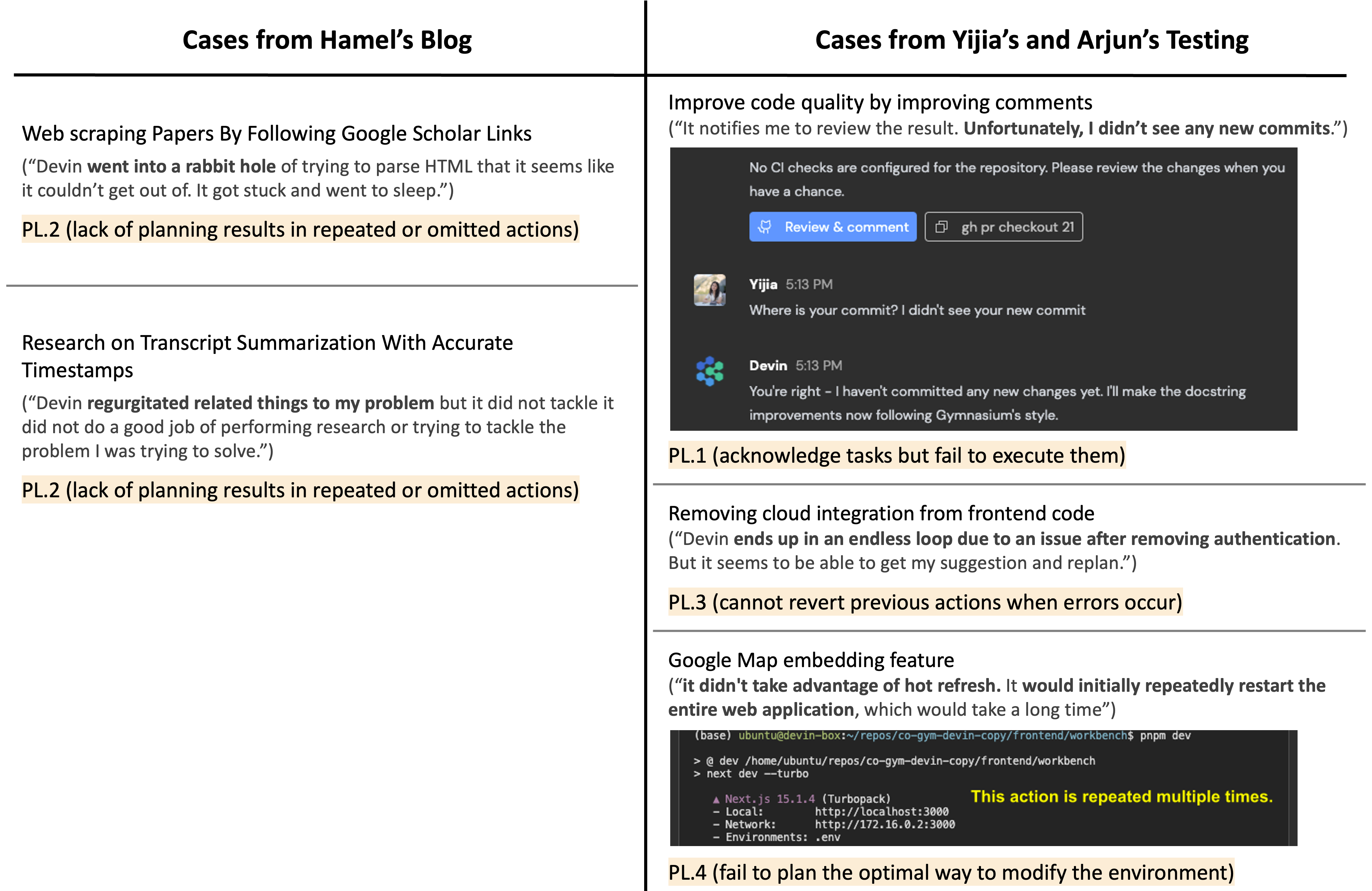

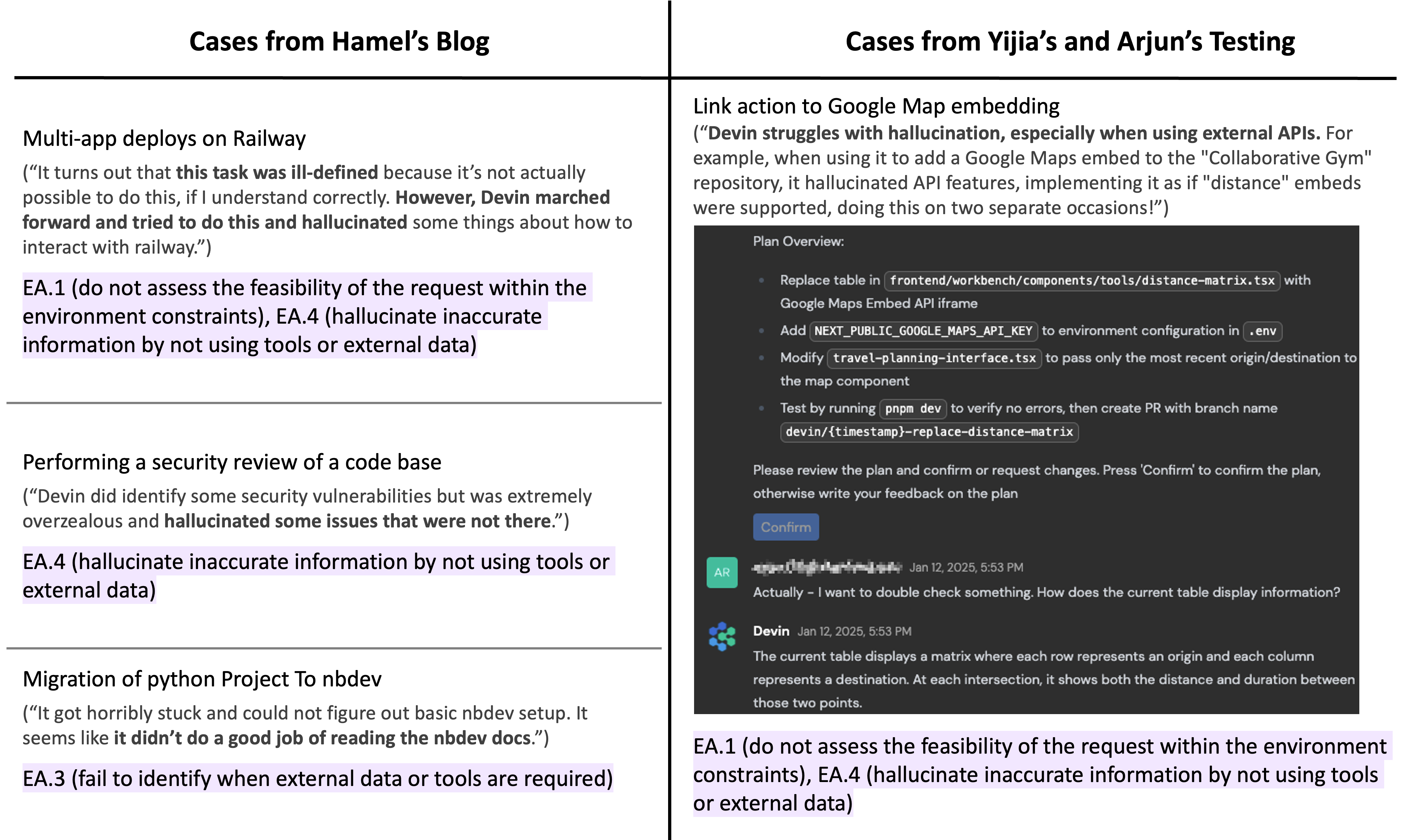

While Hamel’s blog documents their attempts by grouping their cases into three task categories, we plan to apply the taxonomy from our preprint for a deeper analysis to uncover the root causes of these failures. Developed through the examination of real human-agent interaction trajectories and user feedback collected via Collaborative Gym, this taxonomy classifies failure cases into five overarching categories.

Aligning with our findings in Collaborative Gym, failure cases with Devin also fall in these categories:

Communication: Failures in maintaining effective information exchange, that disrupt understanding, coordination, or task execution.

Situational Awareness: Failures in contextual understanding and reasoning about the current state.

Planning: Failures in devising, updating, or executing coherent plans, especially in dynamic or long-horizon scenarios.

Environment Awareness: Failures in recognizing or accounting for operational constraints and resources within the task environment.

Personalization: Failures in adapting behaviors to align with individual user preferences based on in-session histories, and interaction patterns.

We chose to skip this category due to the absence of personal information in the cases discussed in Hamel’s blog. But personalization of LLMs and agentic systems is a very rich and interesting area. Check out this survey if you are interested in learning more.

Opportunity: Building Agentic Systems That Can Collaborate With Users

I still believe that Devin is a solid step in making agents truly useful—kudos to Cognition AI for making it widely accessible—and it remains the only agent I’ve been able to use across multiple sessions so far besides my own work.

While fully autonomous agents can excel in many scenarios, a wide range of use cases necessitate collaboration with users due to users’ evolving preferences, domain expertise, or desire for control, as illustrated in the examples mentioned earlier. Compared with fully autonomous agents, this new paradigm of collaborative agents has shown promising results in our Collaborative Gym experiment, achieving win rates of 86% in Travel Planning, 74% in Tabular Analysis, and 66% in Related Work when evaluated by real users.

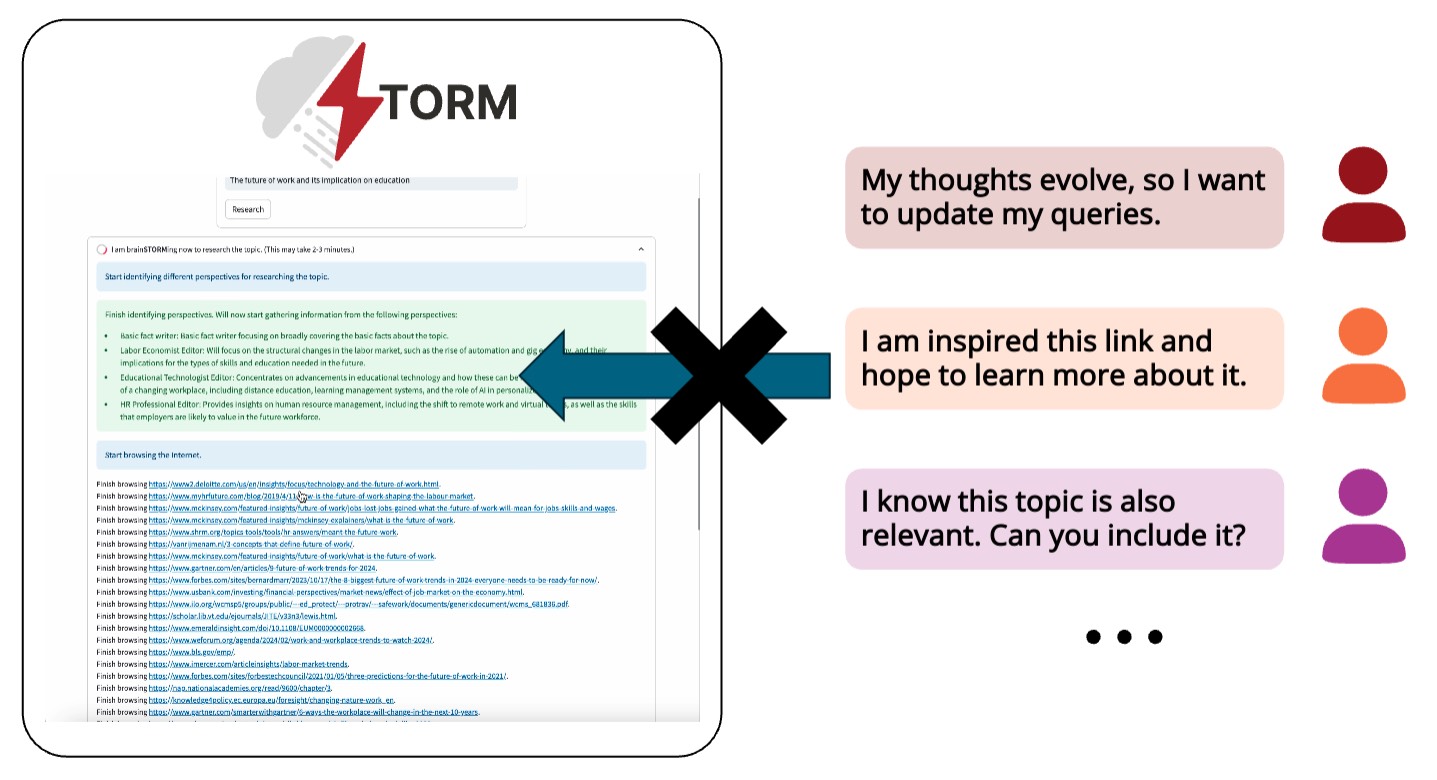

Another example that highlights this opportunity is STORM, an agentic system I worked on last year that writes Wikipedia-like articles through deep research. We noticed a similar tension after deploying the system in real-world settings—despite the strong results reported in our paper, roughly one-third of user ratings for our initial version were at or below 3 on a five-point scale. Many of these complaints stemmed from issues that couldn’t be captured by static dataset-based evaluations, such as: “My thoughts evolve as the agent is working, so I want to update my queries.”

Led by my collaborator Yucheng, we updated the system to Collaborative STORM, a collaborative agentic system that allows users to participate in the agent discussions. The new system is also deployed, and we’ve found it useful not only for report generation but also for facilitating human learning.

One common critique I often get is that pursuing the direction of human-agent collaboration appears more challenging than focusing on fully autonomous systems or benchmarks with static answers. I won’t deny this. As someone trained for standardized exams (including math olympiads) before college, I find that contributing to open-ended, real-world work I’m excited about is indeed tougher than simply optimizing for a test—and the same may be true for machines. Yet these initial results make me super excited about the direction of building agentic systems that has the intelligence to collaborate with users effectively to achieve strong synergy and facilitate human well-beings.

We envision a future where machines act as teammates rather than mere tools. Strengthening both the underlying language models and the agent scaffolding (e.g., memory, tooling) in key areas of intelligence mentioned above, alongside designing a more intuitive UI/UX for asynchronous interactions, seems like a promising path forward.

Acknowledgement

I thank Arjun Inamdar who contributed those cases representing the experience of people who work with a new codebase and seek help from a coding agent. I am also grateful to John Yang for teaching me a lot about coding agents since he joined Stanford. Thanks to Yucheng Jiang for developing the taxonomy used above, Vinay Samuel for providing helpful comments, and to my advisor Prof. Diyi Yang who always supported our exploration.