A very simple way of obtaining information from a series of images is change detection, as described by the formula:

DPjk(x,y) =

1 if |F(x,y,j) - F(x,y,k)| > t

0 otherwise

This results in a binary difference picture, indicating which pixels have changed in intensity more than a given threshold, t , between frames j and k.

However, noise becomes a problem with video images -- individual pixels may change without an actual change to the objects in the image. There are two ways to make the difference detection process more robust. One is to make "super-pixels" by averaging larger squares of pixels before calculating the intensity change. However, the resulting image is grainy. The other method is to use a pixel mask and examine the box of pixels around each individual one to calculate the difference values.

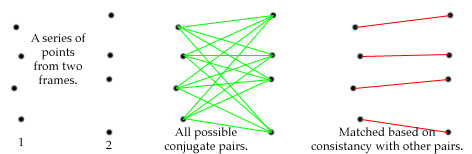

The next step in the process of computer vision through motion is motion correspondence, or grouping the elements of the image series into meaningful features over time. Two methods for locating these distinguishing features are: (1) region based, like the "super-pixel" region described above, or (2) through time-varying edge detection -- examining the edges of an image over time. But, we need a constraining method, like epipolar lines in binocular stereopsis, so that we can effectively find these corresponding features. Otherwise there are just too many possibilities for corresponding features between images.

- Relaxation Labeling

Relaxation labeling is one approach for limiting the possible corresponding features in an image series. By limiting matches based on discreteness of the points in question, similarity, or affinity between the two features, and the consistency that one set of points has with its neighboring pairs, we can come up with a probable approximation of motion in the image:

Image flow is the velocity field of an image due to the motion of the observer or objects it contains. Feature based determination of image flow is impractical, given the number of possible points to match. The more common approach is a gradient-based one, where the temporal and spatial intensity gradient of a series of images is measured. It is based on the idea that the changes in intensity over time, as an object moves relative to the camera, will be gradual. When there is occlusion in the scene -- one object moves in front of another -- this gradient is interrupted.

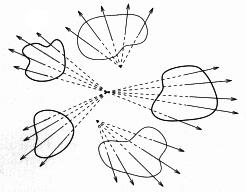

- Focus of Expansion

In a situation where the camera is moving forward, the image flow contains a Focus of Expansion point, as shown in the figure below:

All of the velocity vectors of the images in the scene will meet at the F.O.E. if the object is stationary. Moving objects will have a different direction of image flow. The depth, z, of a point can be determined from its horizontal displacement in space and the velocity of the observer.

One application of computer vision in motion is an automated highway system -- cars that drive themselves. Researchers from Carnegie Melon University's Navlab group developed RALPH (Rapidly Adapting Lateral Position Handler), a system to steer an automobile. With a driver controlling acceleration and braking, RALPH steered 2797 of 2849 miles across the United States (98.2%), in a trip dubbed "No Hands Across America."

In the sample below, the white trapezoid represents the part of the road that RALPH considered in making his steering decisions. In RALPH's case, the position and velocity of the camera are constant, simplifying that process. The program used was robust enough to steer the car if any parallel markings were visible on the road. Lane markers were the obvious choice for such markers, but RALPH was able to adapt to oil stains, sides of the road, and even trucks far ahead to aid in steering.

The process was simple: the pixels in the white trapezoid were converted into an overhead image, indicating the curve of the road ahead. To determine curvature, RALPH generated several test images, distorting the top lines of the image for different levels of turning.

By then summing up the intensity of the pixels of each column in a graph, the program was able to measure the image that had the sharpest discontinuities, and thus the straightest vertical features, and then calculate a turn based on that information.

RALPH also compares the current scanline profile with its current template, and is able to calculate the lateral shift necessary to stay in the middle of the lane. The template can be set either from RALPH's library, manually set by the driver, or dynamically determined based on the top rows of the trapezoid.

For more information, visit Carnegie Melon University's AHS web site for No Hands Across America.