Idea of Visual Perception

Human Perception

Computer vision is all about trying to make a computer take in an image and make

sense of it. Just like you can look around at something or some things and make

judgments about what you see, we'd like a computer to be able to do the same

thing. This process of seeing may not seem like a difficult task at all. If you

were asked to write a 25 page

paper or watch a sunset, chances are you'd pick watching the sunset. Despite

this fact, seeing is not really as easy as we may think it is. It comes easily

to us because it is an unconscious process, whereas writing, for example, takes

conscious effort. In viewing an image, the retina of the human eye performs the

equivalent of close to ten billion calculations per second before sending that

image to the optic nerve. It contains about one hundred million rods and cones,

and the eye itself contains four layers of neurons other than the retina. In

addition, an image is hardly simple itself: as M. Waldrop describes in his book

Man-Made Minds, "depending on what part of [a picture] you're looking at,

the actual intensity of light and color at your chosen point is a function of the

color and texture of [that part], the orientation of the patch of surface, the

color and intensity of the lighting, the direction of the lighting, the

transparency of the intervening atmosphere, the position of shadows, ad

infinitum." (Waldrop 89) Moreover, the eye does not simply scan over an image

and ignore the consequences (like the passive operation of a camera) -- instead

it analyzes the information it receives as well. The human visual process

determines whether a small object in its line of sight is actually small or just

far away by processing information about a 2-Dimensional picture to a 3-D form.

It can also recognize a type of object regardless of what form it may be in -- a

small chair, a swivel chair, a purple chair, an armless chair, etc. are all

perceived as chairs. Humans can also perceive from memory. If you're driving at

night and an oncoming car's headlights impair your ability to see the road, you

can continue driving because you can remember where the road is supposed to be.

Or, if somebody throws a ball into the air and sunlight blocks your view of it,

you don't walk away assuming it's disappeared forever -- you know it will come

back down. Clearly, millions of years of evolution have created a visual process

that is extremely intricate.

As a result, teaching a computer to see in the same way that humans see is not an easy project.

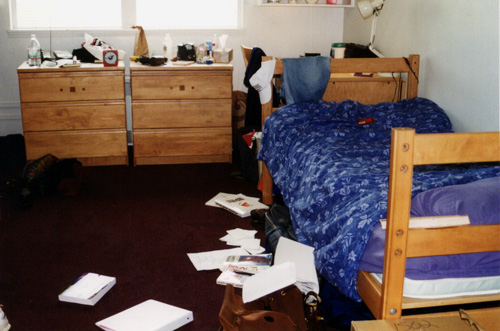

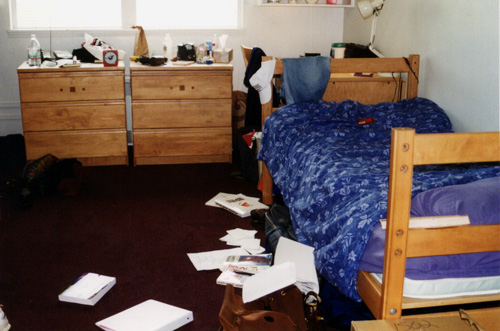

- The Dorm Room Example

Take a look at this picture of a dorm room. We can immediately identify most

things in it, from the mess on the floor to the lamp in the corner. A computer

has no abilities like that. It can't even tell that this is a room -- it's just a

series of pixels.

To be more specific: consider this one element of that picture. As humans, we can

instantly identify it as a clock... but how did we do it? What would you tell a

computer that the features of a clock were, to help it identify one? Think about

what it is that tells you this is a clock. Most likely, you would say it has a

familiar, clock-like rectangular shape and size, an hour and minute hand, and most importantly, it has

numbers that you know tell time.

But what about this picture? It too is a clock, but compared to the first clock,

it has a different, round shape, it's smaller, and it doesn't even have the same

number set-up. It is a completely different representation of a clock from the

previous picture, yet you know this, too, to be a clock.

Think again in terms of a computer, not a human, viewing these two pictures. We

'teach' the computer that the image in the first picture is a clock. Then when

the computer is later shown the second picture and asked to identify the image,

it gets confused. This issue is a simple example of a very complex problem in

the field of computer vision. We have so many different representations and

variations of one given object that it is close to impossible to get a computer

to learn them all. Consider programming a computer to recognize any given type

of automobile. The task is enormous.

The Sensory Equation

The problem inherent in computer vision, in fact, the very purpose of the field,

is to recover information about the world from sensory input. This can be thought

about as a formula: S = f (W). Our sensory information is a function of the world

around us. What humans take for granted, and what the field of Computer Vision

struggles to make machines do, is the reverse: W = f -1(S) -- understand the world

from sensory information.

Back to the Table of Contents.